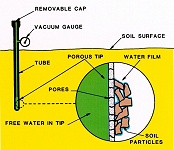

A tensiometer is a water-filled tube with a special porous tip and a vacuum gauge. This instrument measures soil water suction, which is similar to the process a plant root uses to obtain water from the soil.

A tensiometer is a water-filled tube with a special porous tip and a vacuum gauge. This instrument measures soil water suction, which is similar to the process a plant root uses to obtain water from the soil.

Tensiometers are available in various lengths as pictured at left. When installed, only the top of the water-filled tube and the vacuum gauge are visible for readings and  field maintenance as shown at right.

field maintenance as shown at right.

Tensiometers are relatively inexpensive and reusable. They are simple to operate, although they require some maintenance in the field. Maintenance requires the addition of water and the use of a hand vacuum pump to remove air from the tube.

Tensiometers are available in lengths ranging from 6 to 72 inches, allowing installation in the soil at various depths. A single tensiometer measures existing soil moisture conditions only at the depth of the porous tip, and cannot monitor conditions above or below this point. Two or more tensiometers of varying lengths may be installed at one site in order to monitor soil moisture conditions at more than one depth within the root zone.

Soil Water Suction

Water is stored in the soil as a film around each soil particle and in the pore spaces between the soil particles. The water stored in the pore spaces is held by surface tension and is the easiest for the plant to extract. The water film around each soil particle is held by stronger molecular forces and is much more difficult for the plant to withdraw from the soil.

Water from the soil is pulled or sucked into the plant root due to a higher concentration of salts in the plant root. This water extraction process is called “soil water suction.” When the soil is at field capacity, the plant must exert suctions equaling two to five pounds per square inch (psi) to obtain the water it needs. As the soil becomes drier, the amount of suction by the plant must increase to obtain adequate water for its needs.

The permanent wilting point, or death of the plant, occurs when the soil dries to a level that the plant must exert 220 psi or more of suction in an attempt to fulfill its water needs.

In essence, the tensiometer gauges the amount of soil moisture suction required by the plant to extract water from the soil. The dryer the soil, the greater the suction and the higher the reading on the tensiometer vacuum gauge.

When plant roots remove water from the soil and the soil becomes drier, water is drawn from the porous tip of the tensiometer into the soil until a state of equilibrium is reached between the soil moisture and the suction in the tensiometer. Water added to the soil by rainfall or irrigation will reverse this action. The greater suction previously created in the tensiometer will pull water back into the tensiometer and lower the gauge reading.

When plant roots remove water from the soil and the soil becomes drier, water is drawn from the porous tip of the tensiometer into the soil until a state of equilibrium is reached between the soil moisture and the suction in the tensiometer. Water added to the soil by rainfall or irrigation will reverse this action. The greater suction previously created in the tensiometer will pull water back into the tensiometer and lower the gauge reading.

Tensiometers gauge negative soil suctions up to 14.7 psi (100 on the gauge) which is only a part of the available soil moisture. When the soil suction exceeds about 12 psi (80 on the gauge), the film of water covering the porous tip is broken, which allows air to enter the tube. The gauge reading drops sharply, then rebuilds until air enters the system again. When this occurs, the soil must be rewet and the tensiometer refilled before it will again function properly.

As indicated on the gauges to the left, the higher the reading the drier the soil. The gauge that has a reading of 66 would indicate that the plant must exert close to ten psi to extract water from the surrounding soil. The gauge that has a reading of 9.5 would indicate that one psi would be needed to extract water for the soil.

As indicated on the gauges to the left, the higher the reading the drier the soil. The gauge that has a reading of 66 would indicate that the plant must exert close to ten psi to extract water from the surrounding soil. The gauge that has a reading of 9.5 would indicate that one psi would be needed to extract water for the soil.

Tensiometers in Different Soil Textures

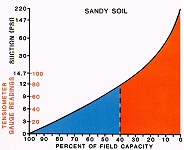

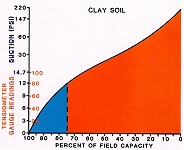

Tensiometers are reliable within certain limitations. For example, the range of usefulness is dependent on soil texture. The finer the soil particles (as in soils high in clay content), the more water the soil can hold, but the harder a plant has to work to draw moisture out of the soil. The coarser the particles (as in sandy soils), the less moisture the soil will hold, but more of the moisture is available for plant use. Tensiometers can, therefore, measure a wider range of available moisture in a sandy soil than in a soil high in clay  content.

content.

In sandy soils, a gauge reading of 80 indicates soil moisture of about 40 percent of field capacity. In sandy soils, most crops need additional irrigation water for maximum plant growth at about 50 percent of field capacity, which is a gauge reading of about 60 on the tensiometer. In sandy soils tensiometers can measure soil moisture from 100 to 40 percent of field capacity because the relatively large pore spaces in these soils release water at lower tensions.

In soils high in clay content, the tensiometer gauge will read about 80 when the soil moisture is at about 75 percent of field capacity. Clays hold water at greater tensions than sandy soils; therefore, the tensiometer breaks suction at a higher moisture level in soils high in clay. When the gauge reads 80, the tensiometer breaks suction and ceases to function. This occurs before the soil is dry to the level that irrigation is required for most crops. Tensiometers can only measure soil moisture from 100 to 75 percent of field capacity in clay soils because the finer pore spaces hold water at higher tensions.

In soils high in clay content, the tensiometer gauge will read about 80 when the soil moisture is at about 75 percent of field capacity. Clays hold water at greater tensions than sandy soils; therefore, the tensiometer breaks suction at a higher moisture level in soils high in clay. When the gauge reads 80, the tensiometer breaks suction and ceases to function. This occurs before the soil is dry to the level that irrigation is required for most crops. Tensiometers can only measure soil moisture from 100 to 75 percent of field capacity in clay soils because the finer pore spaces hold water at higher tensions.

In MEDIUM TEXTURED SOILS, the range of measurement would be intermediate to the values illustrated for sandy and clayey soils.

The texture of the soil also determines the rate of penetration of moisture from the ground surface to the root zone. Tensiometers can be helpful in determining how much moisture has actually penetrated and how quickly.

Tensiometers With Various Crops

Tensiometers are best used when soil moisture will be maintained at 50 to 75 percent of field capacity such as in high moisture demand crops like corn or vegetables.

They do not gauge the low soil moisture ranges from which crops such as cotton, grain sorghum or other small grains can extract adequate soil moisture. However, when installed early in the season, they can indicate the depth to which roots have developed and are extracting water from the soil.

Installation

Tensiometers are normally installed after the crop is established, and they do not interfere with normal tillage operations during the growing season.

Installation of a tensiometer can be made by driving a standard one-half inch pipe or other coring tool into the ground to the desired depth, then removing it to create a hole of exactly the right size and depth for the tensiometer. According to the manufacturers, this method assures good contact between the soil and the instrument with minimum damage to existing roots and soil structure.

Tensiometers are installed in a tight-fitting hole, then a vacuum pump is used to remove air from the tube. The gauge on the vacuum pump is also used to check to make sure the gauge on the tensiometer is functioning properly.

Tensiometers are installed in a tight-fitting hole, then a vacuum pump is used to remove air from the tube. The gauge on the vacuum pump is also used to check to make sure the gauge on the tensiometer is functioning properly.

Detailed instructions for proper installation are provided by tensiometer manufacturers. However the tensiometer is installed, it should be done with minimum disturbance of the soil structure typical of the site. Installation into a large diameter hole and then backfilling is not recommended.

For furrow or flood irrigation, the stations may be placed about two-thirds of the way down the run. If the run is especially long, however, a station at each end of the field may be needed.

The important points in choosing placement of tensiometers for sprinkler irrigation are that obstructions do not exist between the sprinkler and the tensiometer and that excessive water is not concentrated at the point of installation.

Record Keeping

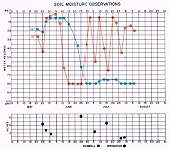

The success of any soil moisture monitoring system lies with careful record keeping. Over a period of time, the irrigator will better understand the readings and variations. The following is an example of a graph which shows the effect of rainfall, cool weather and moisture penetration.

Records throughout the growing season reveal the effects of irrigation and rainfall on soil moisture conditions. Notice that the 12-inch depth reading responded rapidly to rainfall and irrigation in June and July, however, the 36-inch depth reading was unaffected by these events.

Records throughout the growing season reveal the effects of irrigation and rainfall on soil moisture conditions. Notice that the 12-inch depth reading responded rapidly to rainfall and irrigation in June and July, however, the 36-inch depth reading was unaffected by these events.

Disadvantages

The main disadvantage of the tensiometer is that it can only operate when the soils are relatively wet. Additionally, the instrument should be read daily when crop water use is high to detect false readings due to air bubbles entering the tube. Temperatures below freezing can also seriously damage the tensiometer. It must be removed from the ground and stored before temperatures drop to freezing.

Portable Tensiometers

Portable tensiometers are also available. They incorporate a small porous ceramic sensing tip that minimizes reading time. It allows the user to take quick spot-check readings in varying locations. They are very sensitive. Therefore, it is easy to introduce error into the measurements. They also require more maintenance and care in handling than permanently installed tensiometers.

Acknowledgements

This information was written by Mike Risinger, USDA-NRCS and Ken Carver, High Plains Underground Water Conservation District No. 1